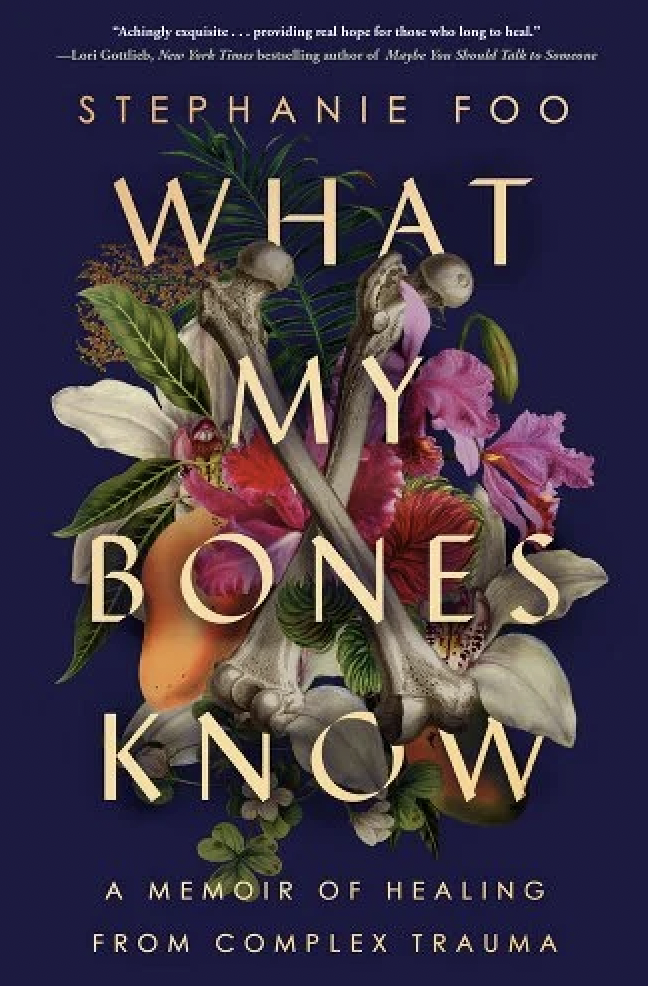

On September 20, Stephanie Foo, author of What My Bones Know, will be joining us to teach for our newest series, THE COURAGE TO WRITE FEARLESSLY, on the topic of “getting it right,” and how to overcome the intellectual and emotional obstacles to that particular expectation when you’re writing your memoir.

I adored this book, which was what prompted us to invite Stephanie to teach for us in this series. Some of the things Stephanie wrestled with getting right, she shared with me, were being a representative voice, both for people with C-PTSD (Complex PTSD), the diagnosis she reveals to the reader she has at the outset of the book, and also for Asian-Americans who, like her, might suffer from trauma linked to shared family and cultural experiences.

Memoir writing requires courage, so much in fact that I’m often in awe, as a reader, of the stories and experiences I am invited to peer in. Given my work with memoirists, I know intimately that digging into past experiences, emotions, and traumas is heart work. It’s mind-body-spirit work. It sometimes costs the memoirist a lot, and there are a million thoughts and niggling fears that memoirists have to grapple with alongside the hard work of executing their scenes and reflections.

The fear of getting it right is not a fear reserved for perfectionists. It’s one we hear in our classes all the time—when people don’t necessary remember what happened; when writers are nervous about the way they’re characterizing others, especially if they’re showcasing problematic behavior; and then more broadly when, like Stephanie, they’re working with experiences or diagnoses that are theirs but also belong to others. Our students have shared that they worry about being the voice for their communities, or that they’re scared of fallout. When Firoozeh Dumas, author of Funny in Farsi, taught for our Women Writing Memoir series last fall on the subject of shame, she touched upon the same fear of representation that Stephanie shared. For Firoozeh, in writing about her Iranian culture and family, she felt vulnerable exposing things that her fellow Iranians might deem to be disrespectful, or that showed the dark underbelly to people everywhere, or that aired dirty laundry. These are fears memoirists must contend with—for the fallout can be very real. Memoirists do sacrifice a lot in order to write the truth of their experiences, and still, by and large we hear from published memoirists that it’s worth it.

There are antidotes for the fear of getting it right. What follows are three places where we see memoirists harangued by their desire to do it the “right way,” and some corresponding reminders you can give yourself when your anxieties start to flare up:

1. Fear of getting the facts right

Reminder: Give yourself permission, over and over and over again, as you write and edit your memoir. In our courses, we preach the gospel of emotional truth. We remind our students often that it’s not factual veracity that matters so much in memoir, but rather emotional truth. What you write on the page needs to have happened, but the contours of what happened must be filled in by what “probably would have been” or what you know to be true based on your upbringing, having lived your life, and what you know about the real people who populate your book. Dialogue needs to be recreated, and composite scenes are allowed, so as much as memoir is “true,” it is also creative nonfiction—and the creative part requires you to fill in the gaps and to interpret what happened.

2. Fear of representation (being a voice for your community)

Reminder: There are more people from your community (and we’re talking racial, regional, religious, gender- or sexual-identity, being a survivor—there are many communities we represent) who will resonate with your truth than deny it or balk at it. None of us aspires to be the poster child for our communities when we write personal narrative, but there’s also no way to avoid it. Rather than bemoan this reality or rail against it, write as if your community were embracing everything you have to say. Remember the ones you’re writing for, who need to read your words and hear your message. Write like you have nothing to lose, and work out the details of what might need to be removed in a much later draft.

3. Fear of how others will react and if their truth will align with yours

Reminder: Don’t share with people in your intimate circle who might contradict your truth. Write for yourself at the outset. Trust yourself, and hold tight here to emotional truth as well. Your characterization of events might differ from your parents’, your siblings’, your friends’, your extended family. Fear of being “wrong” or of hurting people’s feelings, or of being called a liar, or of not having your truth validated are all stones that fall into this particular bucket of fear. Stay the course. Connect to your heart center. Remember that we all see the world through a particular lens, and your memoir is your personal truth through the lens of your interpretation. Your truth might indeed upset people, and if this is the case, you must ask yourself if you’re willing to risk that upset. Remember Audre Lorde’s words of wisdom here: “When we speak we are afraid our words will not be heard or welcomed. But when we are silent, we are still afraid. So it is better to speak.”

We hope you’ll join us to hear Stephanie Foo on September 20 speak about her experience of writing her incredible memoir—which circles abuse and trauma, her C-PTSD diagnosis and therapy, her desire to understand her reactivity in order to be the best version of herself, and also the pressures on Asian-Americans growing up with immigrant parents and the sense she makes of this macro experience alongside her very specific abusive upbringing. Not to be missed, and the book is a must-read.

Speak Your Mind