Memoir, as a genre, requires intimacy and self-exposure. It demands confession and deep dives into the truths of our inner lives. When we write a memoir, we enter into a contract with the reader: we’ll reveal the truth of our experiences, our emotional truth. But how much? How detailed? And what are we allowed to hold back? These are questions all memoirists encounter, especially at the beginning of the writing journey.

Memoir, as a genre, requires intimacy and self-exposure. It demands confession and deep dives into the truths of our inner lives. When we write a memoir, we enter into a contract with the reader: we’ll reveal the truth of our experiences, our emotional truth. But how much? How detailed? And what are we allowed to hold back? These are questions all memoirists encounter, especially at the beginning of the writing journey.

Another question every memoir writer will face has to do with exposure—how much and how detailed to be in what you reveal. I don’t know any memoir writer who doesn’t wrestle with the anxiety of deciding what to confess and what to hold back; how to write about the people in our story with whom we share deep intimacies. Love and pain. Joy and wounding.

In the beginning, all we have to work with is our swirl of memories, ones that will eventually become scenes on the page. In this first stage, it’s important to explore the territory of your story, to take time to figure out what happened when, and to determine the significant moments that form the basic spine of the memoir.

Writing a memoir is an act of exploration—it’s an archeological dig, surfacing aspects of self and relationships that have been buried in the vaults of memory.

It’s important to write fully and honestly from the beginning and to try to table your fear of repercussions. Don’t show your work to anyone but your most trusted memoir writing pals. Early drafts of your work, which is deeply psychological in nature, needs protection. Treat it like a fragile plant and give it room to grow. Don’t show it to your family or to anyone who features prominently in the memoir!

If you’re writing about trauma or secrets, your inner critic will start to berate you, and you’ll need to tame it—to ask it to leave you alone so you can write messily and honestly. Tell it that no one will see what you’re writing for a long time.

There are also containment techniques to keep traumatic memories from retriggering you emotionally.

These include:

• Creating lists of the darker moments you lived through instead of launching in and writing what happened at once.

• Writing any given painful scene for only ten to fifteen minutes at one time, then returning to the life you are living now.

• Making lists of the happier, more positive moments in which you were able to find relief, comfort, or happiness. Who helped you? Who witnessed who you were then—a teacher, a counselor, a neighbor, a friend? How did you soothe yourself when there was pain—through reading, music, nature, pets, friends? Those moments of hope and compassion are important parts of your story, too.

• Diving into your deepest fears as a way to mitigate how powerful they are. Write down all the reasons NOT to write your memoir and explore them. Get your doubts onto the page where you can look at them objectively. List your fears—each one.

These might include:

• Moments that feel shameful.

• Things that happened where you felt judged or where you judged yourself.

• Things you did that you hate yourself for, that you can’t admit that to anyone.

• Incidents in which you feel so exposed and vulnerable that it makes you wonder if you can write your story.

Extract these very valid concerns from the shadows and bring them into the light. Write about each thing that silences you. Explore these issues from all angles. Writing in private is the first step to find clarity.

Once you have your list, make another list of all the reasons why you want to write your memoir, all the reasons you must. These are your antidotes, and you may need to hold onto them tightly, to revisit them over the course of your writing process.

It’s ironic but true that naming our fears often diffuses them, giving them a little less of a stronghold. The process of writing a memoir is never without any fear, which is part of why it’s such a courageous thing to do.

We need to be in dialogue with ourselves through our writing, however, and not try to strongarm our way to the end. Writing your memoir is an act of deep compassion that we enter into—for ourselves as well as others. So be gentle with yourself, and also know that you’re not alone.

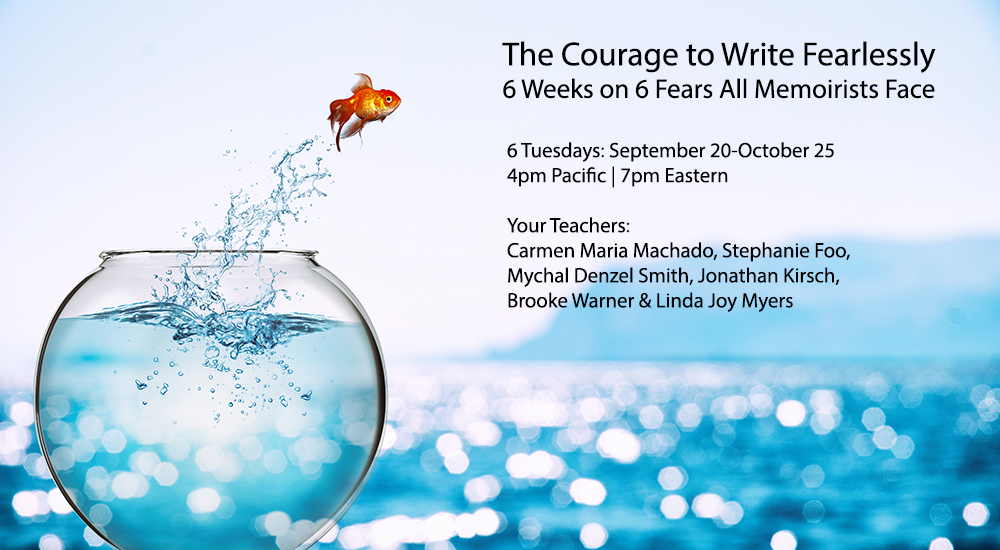

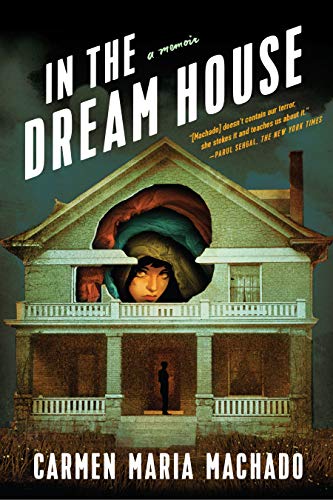

We hope you’ll join us to hear Carmen Maria Machado on October 25 (part of our COURAGE TO WRITE FEARLESSLY series) teach and speak about exposure—which she handles so deftly in her memoir, In the Dream House. Machado’s portrayal of intimate partner abuse is both troubling and stunningly rendered on the page—and the number of considerations for what and how to write about love and abuse, gaslighting and undermining, and so much more will be among the subjects she circles in her class.

In writing my own memoir, I rested upon a phrase from Ernest Hemingway when he had difficulty beginning to write. Aside from the assurance that one knows he/she can write and write well, he added: ” To begin write one true sentence.”

A simple declarative sentence to begin, both as a start but also as a ‘hook’ line for me the writer. I did that, and the next 40 pages followed.

Within that I realized, the truth is a freeing instrument. I felt assured that even the more intimate items would receive their fair and just due. That truth enables the heart to breathe.